Your gut microbiome is a microscopic world within the world of your larger body. The trillions of microorganisms that live there affect each other and their environment in various ways. They also appear to influence many aspects of your overall health, both within your digestive system and outside of it.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/Images/org/health/articles/25201-gut-microbiome)

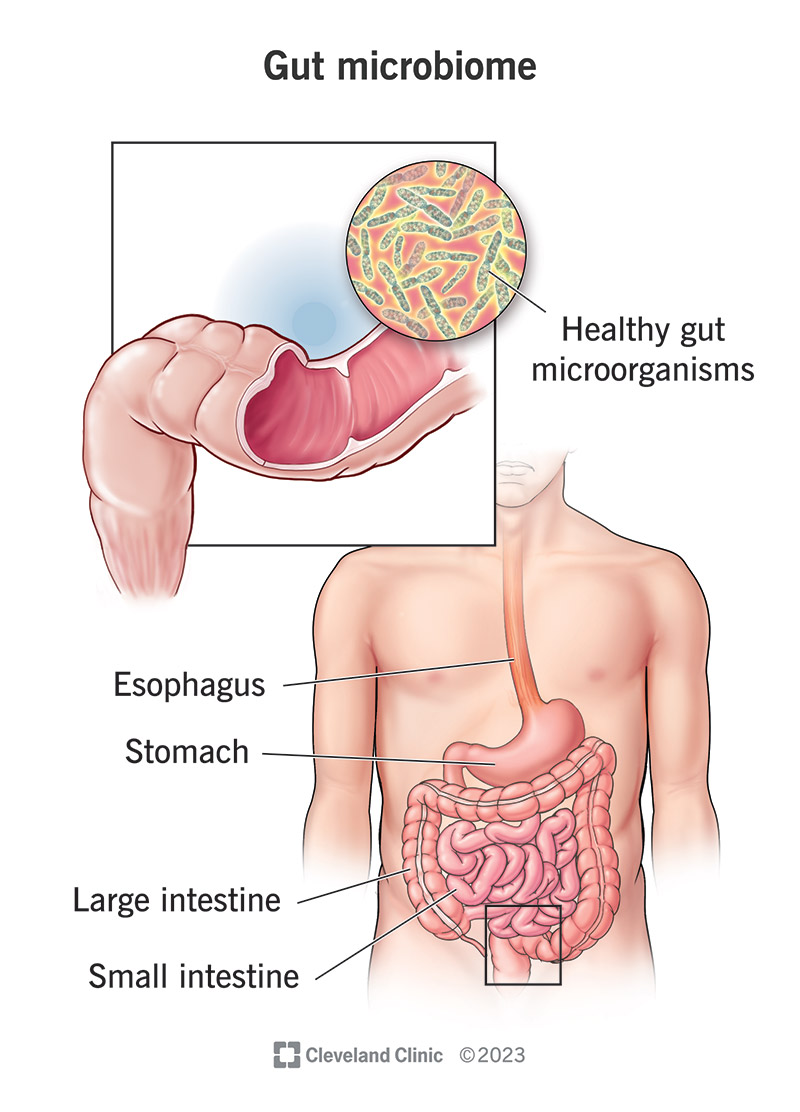

A biome is a distinct ecosystem characterized by its environment and its inhabitants. Your gut — inside your intestines — is in fact a miniature biome, populated by trillions of microscopic organisms. These microorganisms include over a thousand species of bacteria, as well as viruses, fungi and parasites.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Your gut microbiome is unique to you. Infants inherit their first gut microbes during vaginal delivery or breastfeeding. Later, your diet and other environmental exposures introduce new microbes to your biome. Some of these exposures can also harm and diminish your gut microbiota.

Most of the microorganisms in our guts have a symbiotic relationship with us, their hosts. That means we both benefit from the relationship. We provide them with food and shelter, and they provide important services for our bodies. These helpful microbes also help to keep potentially harmful ones in check.

You can think of your gut microbiome as a thriving native garden that you rely on for nutritious foods and medicines. When your garden is healthy and thriving, you thrive, too. But if the soil is depleted or polluted, or if pests or weeds are overrunning the helpful plants, it can upset your whole ecosystem.

Video content: This video is available to watch online.

View video online (https://cdnapisec.kaltura.com/p/2207941/sp/220794100/playManifest/entryId/1_kdlrtniv/flavorId/1_5f3sgelj/format/url/protocol/https/a.mp4)

Christine Lee, MD, explains the gut microbiome.

Your gut microbiome interacts with many of your body systems and assists with many body functions. It plays such an active role in your body that some healthcare providers have described it as being almost like an organ itself. Some of these interactions we’re still learning about, while others are well known.

Advertisement

Bacteria in your gut help break down certain complex carbohydrates and dietary fibers that you can’t break down on your own. They produce short-chain fatty acids — an important nutrient — as byproducts. They also provide the enzymes necessary to synthesize certain vitamins, including B1, B9, B12 and K.

These might seem like small nutrients, but micronutrient deficiencies can have a big impact on your health. (See: vitamin B12 deficiency, folate deficiency and vitamin K deficiency.) Short-chain fatty acids, in particular, feed the cells in your gut lining and help to keep your overall gut environment healthy.

Gut bacteria also help to metabolize bile in your intestines. Your liver sends bile to your small intestine to help you digest fats. When that’s done, bacteria and their enzymes help to break it down so that the bile acids can be reabsorbed and recycled by your liver. This is called enterohepatic circulation.

If this process stopped working, your body would be unable to recycle bile acids and your liver wouldn’t have enough to produce new bile. Your digestive system wouldn’t get the bile it needs to digest and absorb fats. And leftover cholesterol, one of the components of bile, would build up in your blood.

Beneficial microbes in your gut help to train your immune system to tell them apart from the unhelpful, pathogenic types. Your gut is your largest immune system organ, containing up to 80% of your body’s immune cells. These cells help to clear out the many pathogens that pass through it every day.

Helpful gut microbes also compete directly with unhelpful types for real estate and nutrients, preventing them from taking up too much territory. Some of the chronic bacterial infections that can affect your GI tract, including C. difficile and H. pylori, are directly related to having a diminished gut microbiome.

Short-chain fatty acids, the byproducts of helpful gut bacteria, have important benefits for your immune system. They help maintain your gut barrier, keeping the bacteria and bacterial toxins inside from escaping into your bloodstream. They also have anti-inflammatory properties for your gut.

Inflammation is a function of your immune system, but it can malfunction, becoming hyper-reactive. Chronic inflammation is a feature of autoimmune disease and may have a role in many other diseases, including cancer. Short-chain fatty acids appear to suppress these types of inflammatory reactions.

Advertisement

Gut microbes can affect your nervous system through the gut-brain axis — the network of nerves, neurons and neurotransmitters that runs through your GI tract. Certain bacteria actually produce or stimulate the production of neurotransmitters (like serotonin) that send chemical signals to your brain.

Bacterial products may also affect your nervous system. Short-chain fatty acids appear to have positive effects, while bacterial toxins might damage nerves. Researchers continue to investigate how your gut microbiome might be involved in various neurological, behavioral, nerve pain and mood disorders.

Gut microbes and their products also interact with endocrine cells in your gut lining. These cells (enteroendocrine cells) make your gut the largest endocrine system organ in your body. They secrete hormones that regulate aspects of your metabolism, including blood sugar, hunger and satiety.

Researchers continue to explore how your gut microbiome might be involved in metabolic syndrome (obesity, insulin resistance and Type 2 diabetes) and excess fat storage in your liver. These conditions have some relationship with certain gut microbiota, although exactly what it is isn’t clear yet.

Advertisement

Your “gut” roughly refers to your gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Most people use it to mean your intestines. You have some gut microbiota in your stomach and small intestine, but most of them are in your large intestine (colon). They float around inside or attach to the mucous lining on the inner walls (mucosa).

The types of gut bacteria that live in your colon are different from the types that live elsewhere. They’re mostly anaerobic bacteria that require a low-oxygen environment to survive. The higher oxygen, faster movement and strong digestive juices in your upper GI tract prevent them from colonizing there.

Anaerobic gut bacteria perform important functions within your colon that only they can. They help break down indigestible fibers in your digestive tract and produce essential nutrients that you can’t get otherwise. By the same token, these organisms are only helpful to you within their natural microbiome.

If these bacteria stray beyond your colon, they can be harmful. Colon bacteria that manage to creep up and settle in your small intestine can interfere with digestive processes there. Colon bacteria that invade your colon wall, or that escape through a wound in your colon wall, can cause an infection in your body.

Advertisement

Healthcare providers use the term “dysbiosis” to refer to an unbalanced or unhealthy gut microbiome.

Dysbiosis means:

Dysbiosis may start with one of these three factors, but the others tend to soon follow. A loss of beneficial bacteria leaves your gut vulnerable to more disease-causing or invasive types. These types can overrun the other microorganisms living there, disrupting the balance of bacteria in your microbiome.

Just like a garden, your gut microbiome is affected by the nutrients and pollutants, pests and weeds it’s exposed to. The mix of plants and their changing life cycles also affect it. In your gut, this means your diet, chemical exposures, disease-causing organisms and bowel movement regularity.

The variety of microorganisms in your gut microbiome requires a variety of plant fibers to thrive. Different organisms prefer different whole foods. In turn, they produce short-chain fatty acids and other byproducts that nourish your gut and lower the pH inside, which favors the more beneficial microbes.

On the other hand, a diet high in sugar and saturated fats tends to favor the less helpful types of microorganisms. Processed foods not only lack fiber and micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) but also tend to come with many additives and preservatives, which can be harmful to your microbiome.

Chemicals that may poison your microbiome include environmental toxins like alcohol, tobacco smoke and pollutants. Additionally, pesticides like antibiotics can wipe out the good bacteria along with the bad. Other medications, like acid blockers, can affect your microbiome by changing the pH inside.

Your gut microbiome can usually recover from temporary chemical exposure, like a brief prescription for a medication you need to get well. But chronic exposure can affect its composition. If you take certain medications or use substances like alcohol frequently, it may prevent certain microbes from thriving.

In a healthy gut microbiome, different types of microorganisms support each other. Consider how different plants in a garden cross-pollinate or nourish the soil for each other. For example, some types feed other types by breaking down compounds, or their byproducts change the acidity of the “soil.”

On the other hand, a microbiome that doesn’t support a healthy variety of microorganisms is more vulnerable to being overrun by the invasive types. Without healthy competition, these “weeds” and “pests” take over the habitat and deplete the resources that the other types need to survive.

Your motility is the regular movement of your bowels. This is how your “crop” of microorganisms turns over. After traveling through your colon, where they help break down undigested compounds into nutrients you can absorb, many come out with your poop. How long this takes affects your microbiome.

The movement of food and waste through your GI tract helps to distribute different microbes into different places along the way. If it’s too fast, they don’t have time to settle or to do their jobs before clearing out. But if it’s too slow, they can overeat and overgrow, spreading beyond their territory.

Conditions directly related to gut dysbiosis include:

Other conditions that may be indirectly related to gut dysbiosis include:

Typical symptoms of gut dysbiosis include:

Many commercial labs offer gut microbiome testing kits to consumers. You can send a poop sample to a lab, and they’ll send you back a report telling you a little bit about the composition of your gut microbiome. Clinical healthcare providers generally don’t use or recommend these tests, though.

The reason is that we still don’t know enough about the different types of gut microbiota or how they affect our health to make a report like this useful. There’s a lot of exciting research in progress, but it has some ways to go before a gut microbiome test can give you practical, personalized healthcare advice.

Healthcare providers don’t check for dysbiosis, per se, but they can check for specific conditions, like infections and bacterial overgrowth. They may use blood tests, stool tests or breath tests. A breath test can measure different gases in your breath that are the byproducts of certain bacteria in your gut.

Some medical treatments for your gut microbiome include:

A healthy diet and lifestyle encourages a healthy gut microbiome. For example:

The gut microbiome is a hot topic these days in medical and wellness communities, and it’s easy to see why. These critters seem to have so many tentacles in so many different body systems that it’s possible to imagine they might hold the key to understanding and treating a wide range of intractable diseases.

As research continues, healthcare providers are both optimistic and cautious. The more we learn, the more we realize how much there still is to learn. But what we’re learning also goes backward to confirm some of our oldest wellness principles. In particular: a healthy, whole foods diet is key to a healthy gut.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

If you have issues with your digestive system, you need a team of experts you can trust. Our gastroenterology specialists at Cleveland Clinic can help.